On the compulsion to make art

Peatery in Drenthe, Vincent van Gogh, 1883

In the 1930s, people on the island where we live would go down to the old coal pit after thunderstorms, the village historian told me. They went looking for pink fragments of stone, the size of a finger—fossils after a kind of 120-million-year-old squid that had been hauled from the ground by the miners. But the villagers thought the pink stones were the arrowheads of lightning that had struck, and they would put the lightning tips they gathered under their beds to keep themselves safe. Lighting will not strike the same place twice.

There was still a thin drizzle in the air when, after the next rain storm, our four-year-old and I parked our bicycle next to the coal pit. There was no life in sight: it was all sooth and sand, a black desert. A century after the production had closed down, not a single straw of grass. The rain, pouring in thin streams, had carved the black sand into a labyrinth of ravines.

We walked the labyrinth toward the sea. I told Maud that this is what the earth must have looked like 500 million years ago, before life seeped and wriggled out of the sea and conquered land.

Rolling down the walls of the ravines were scraps of coal, few of them larger than my thumb. The village historian had told me that a sculptor, a stone cutter, who lived nearby, used to go down here in the winters to collect these scraps of coal to heat his house. In the early 1960s, when he was in his twenties with two kids and few prospects of selling his art, he had been brought to such financial despair that he could be seen out here with a wheelbarrow, crawling on his knees.

In the years after I heard about the sculptor scavenging stone coal by the sea, I began collecting information about him. When artists who had known him came into the gallery where I worked, I would interview them. I looked for pictures of his sculptures. In our archives, I found a self-published book he had made and read what he had written.

These, our first years on the island, were, as I’ve written elsewhere, difficult years. Johanna and I had two young children, whom we raised at home. To have time to write, I would go up at 5 am and write until 9, when I took care of the kids until I had to bicycle down to the art gallery, where I built exhibitions and did the bookkeeping in the afternoons. I remember us climbing with lamps on the roof, late at night, tarring the wood on the new roof.

It was, I think, in order to handle the exhaustion and loneliness I felt, that I began collecting stories of local artists who had struggled and seen little external reward. It felt good to know that we weren’t alone, even if no one Johanna and I knew shared our obsession and were willing to make the tradeoffs we made. These landscapes had known others like us. There had been an autistic farmhand who spent his spare time painting the fields around our village; his paintings were discovered when he was 61, a year before his death. There had been a homosexual German art collector who had fled the Nazis and hid in a boat house, where he hung the walls with Matisse and Kandinsky. At the local museum, I had bought a stack of postcards of paintings done within walking distance of our house, and I kept them on my writing desk.

All of the artists had been outsiders. They had not been part of a scene. But when you grouped them, they looked like a constellation—like lone suns, hung in infinite darkness, that from afar revealed themselves to be part of the same pattern. It was a pattern of people with a compulsive need to look at the landscapes around them, at their small life worlds, and to capture what they saw. I imagined myself and Johanna as a part of the constellation and took comfort in that.

I knew that artists always struggle with poverty and social ostracisation, unless they are born wealthy. But whenever I read about famous writers or painters or filmmakers, it was hard not to read the stories of their hardships in the light of the fact that they would eventually succeed. And I couldn’t relate to that. It is cute when someone calls a plumber and then gets shocked when the American composer Philip Glass appears to fix their toilet. Well, how do you expect artists to pay the rent? But it is cute, precisely, because Philip Glass is Philip Glass and will eventually have his operas playing on every continent.

I found much more comfort in the stories of artists who fixed toilets but never got famous, and who did it anyway. It helped me remember that that cave man desire to populate the earth with your art is normal.

The sculptor had moved to the island in 1957. Looking for a place with good granite, he and his wife, K, both young art students, had bicycled around the island, looking at old farms. The one they bought cost 18,000 kroner (about $30k, inflation-adjusted). It lacked electricity, running water, and sewer.

By the time they moved in, their first daughter had been born. The daughter, who later married a Japanese stone carver who came to study her father’s work, says growing up with two working artists was, despite the poverty, a beautiful experience. “It felt like we [kids] owned the forests, the fields, the cliffs, and the small ponds with salamanders.” “Dad would always whistle Bach while he worked.”

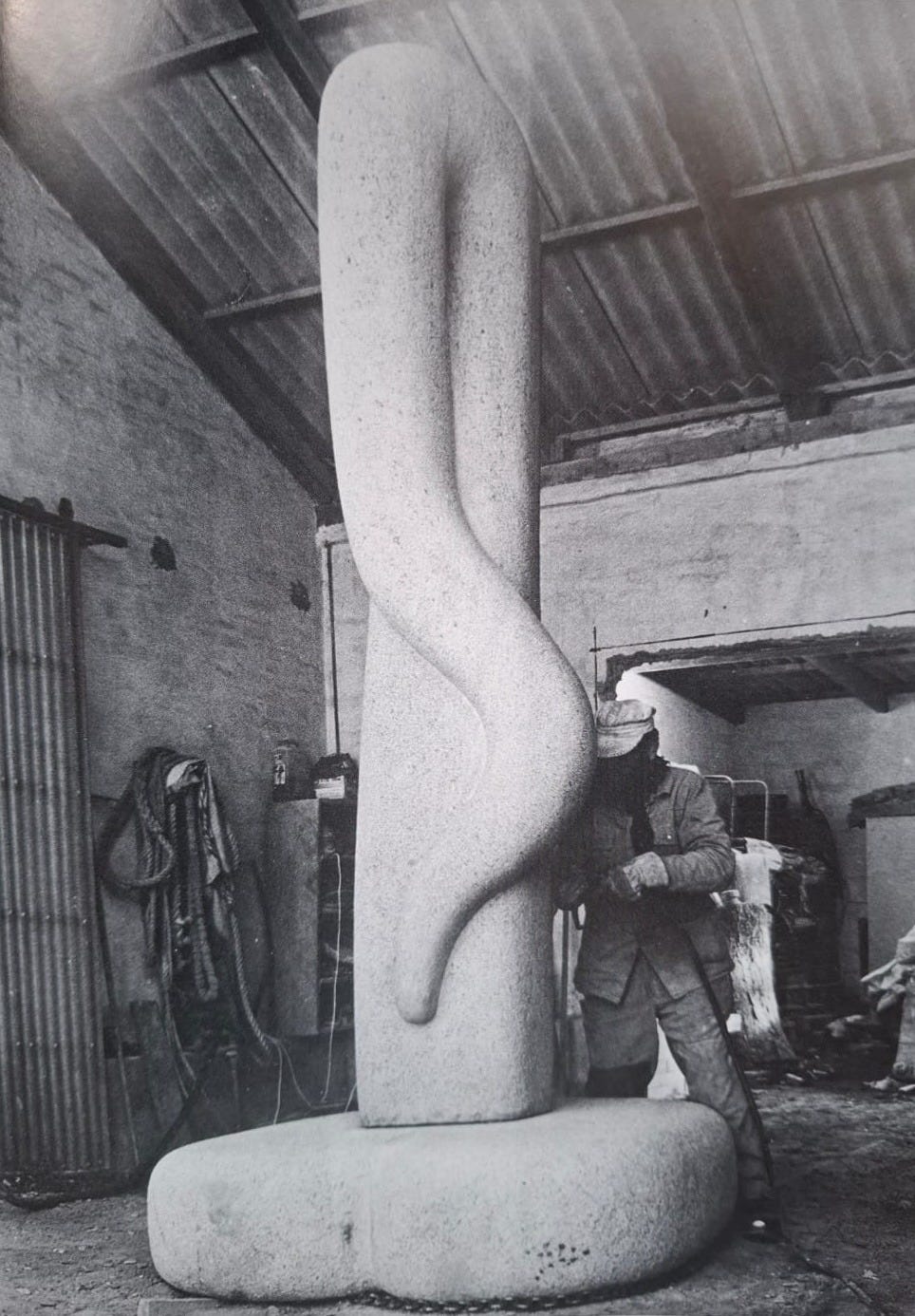

In 1961, the family had grown to four, and their annual income was 1,800 kroner ($3k, inflation-adjusted). Their daughter says the municipality refused to believe that they could survive on that. But they kept sheep for milk, meat, and fur; they grew what they ate; and the granite for sculptures, the sculptor quarried himself on the farm and pulled without machines, using rolling logs and pulleys.1

The sculptor’s wife, in an interview in 2004, says he had an unfathomable capacity for work. He would rise early, eat breakfast with the kids, and then work in the quarry or carve or tend the farm until lunch, when he’d sleep—as the old stone cutters he had apprenticed with would sleep each lunch, sitting up—before going out to work until dusk.

A local art historian, who knew the family, says, “The only thing that could keep him from the stone was if it was so cold that he couldn’t be in his workshop. Then he would sit inside and work with clay instead.”

The work was what kept him connected to himself and to the life force he felt in the world. “The more you work, the more things come to you. It’s a very amusing function,” the sculptor writes. “You get into a good circle, where the more you make, the more you can do, and the more ideas come to you. And conversely, if you’re away from it, it’s very hard to get going again. And your stomach starts to hurt, and you get depressed. Then you just have to throw yourself into it, but that can be hard. … I love the feeling of stone dust between my teeth after a long winter.”

Describing the work with the clay, he writes that he would sit with his eyes “almost closed,” feeling the shapes take form in his hands. When a shape gave him a deep tactile pleasure, he would open his eyes and study what had happened. “I fill both my warehouse, but also my head with experiences of form, so that I can scoop freely from it [when I stand before a rock to be carved]. And the fact that I’ve had the form in my hands means I can remember them much better.”

He spent a lifetime exploring which shapes spoke to his hands, the hands of this particular man, who loved children and nature and who will not be mentioned in the history books. Then he took these small, intimate, and often sexual feelings and made them permanent as rocks.

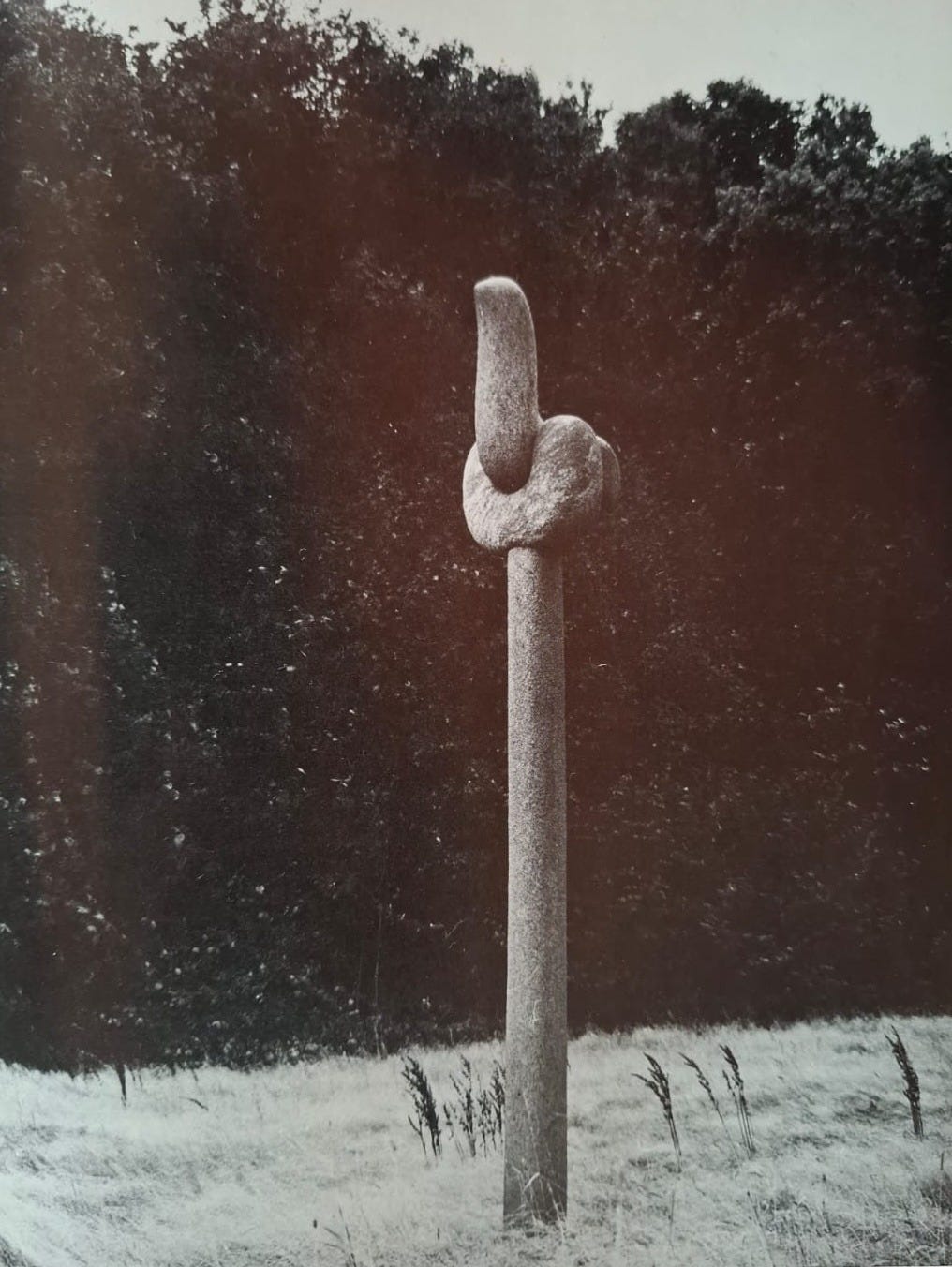

“If you look at the cliffs that have been carved by the glaciers during the ice age,” he wrote, “you can still see the carvings there 10,000 years later—so these shapes will live on for a long time.”

The feeling of a hand in 1972 made into an object that will stand for millennia… It is hard not to see a parallel to some of the oldest preserved cave paintings, which are hands that have been held up against the cave wall and preserved as silhouettes by color pigments blown at the hand. We were here; we felt this.

In the late 1960s, the sculptor began working with a local factory that produced sewage pipes. In the winters, when his workshop was too cold for him to carve stone, he would go to the factory and pick up unburned clay pipes, place them in his living room, and start bending and reshaping the pipes into sculptures. When he delivered them back to the factory to be burned in their 100-meter-long tunnel kiln, there would come a glimmer into the workers’s eyes as they offered knowing assessments of the sculptures—often abstract penises or vaginas, or abstract penises penetrating abstract vaginas. Again: like cave art. The workers were delighted to participate in an art project like that.

There was no economic logic in doing what the sculptor did. But it spoke to a deep human need. We need sewage pipes, yes, but we also need to honor the sense of aliveness that rushes through us. As in the apocryphal story about a legislative session during the Second World War, when someone suggested cutting the arts funding to support the war effort, and Churchill answered, “But then what are we fighting for?” It is ok to sacrifice yourself to the hunger for art; that is what the sculptor’s work says to me.

Some of his works were sold as public decorations, but many just filled the forests and fields where his children played. Their reason for existing was that he wanted to make them.

In 2023, Karen and Mette, two women in their late 70s who volunteered at the art gallery, told me that the sculptor’s farm was still intact. Why no one had told me this before, I do not know. They had been out there in the morning before work, looking at the sculptures, and they giggled when they talked about it.

“You have to go there,” Karen said. “It’s…”

Instead of finishing the sentence, she touched her face in a way that looked embarrassed.

Given that Johanna and I had so much work to do with the gallery and the farm, the kids and the essays, I didn’t have time to search for the sculptor’s farm.

A year passed. I wrote 40 essays, made 24 exhibitions, and tore out an inner wall in our kitchen where I found a mushroom the size of a man.

But then, in October 2024, I found myself with four hours to kill. The air was still warm from summer heat captured in the sea when I got up on my bike and set off in the direction I had been told the farm was.

I rode on the curving paths among hazels, maples, hollies, and oaks. The roads got narrower and narrower, and I spent twenty minutes going down dead ends that led to pig farms and summer houses.

But then the landscape changed: cliffs of granite shot up among the oaks; there was bramble stretching its arms across the road.

Coming around a bend, I saw them. It was a herd of sculptures. They looked primordial, like the remains of a forgotten ice age fertility cult. I saw abstractions of flowers and testicles (“flowers are balls, essentially… so I won’t keep myself from making those even if people go around saying: he’s naughty, that one,” the sculptor had written). I saw a rock that held the essence of a voluptuous woman, a Venus of Willendorf. I saw a giant, four-ton penetration that was, on closer inspection, titled The Priest.

I had already seen some of these works, depicted, but it had not prepared me for the emotional impact of walking into his landscape.

I think the effect came from the deep resonance between the art and the nature it grew out of. The nature around the sculptor’s farm was unusually wild and fecund, with bramble and ivy climbing the trees and mushrooms bursting from the ground. And these forces and forms were mirrored in the art—it was the fecundity of this land, this precise land, that had worked itself into his subconscious and returned as stone. As he wrote in his notes, “It is fantastic to look at, for example, moss and lichens or the smallest flowers through a loupe. Rich independent worlds.” It was here he had spent his life, crawling in the grass, observing the life around him.

But the influence went both ways. By being mirrored in his sculptures, the surrounding nature was changed—it got charged with the eroticism he must have felt for it. The moss, the same moss we have on our farm, here, I felt, was very clearly fornicating, making moss babies, spreading, putting out their forms. The robins sounded like they were getting into it, too. The mushroom caps, with their rich musky smells, revealed themselves as what they are: sexual organs, as did the autumnal pollen blowing in the air—I was surrounded by acts of sex.

Walking to the edge of the farm, I found one of the quarries and thought about the fact that he had carved this world with his own hands. He had torn it from the bowels of the earth. He had quarried and carved stones, and made and fed babies, and quarried again, until, after 45 years, the land had been transformed—had absorbed him.

This essay is a part of series about art works / artists that have moved me. See also:

Later in his career, the financial hardships eased and he could afford to buy granite from an industrial quarry that had closed down. He also acquired machinery, and in the 1980s could even afford to hire an assistant.

"I found much more comfort in the stories of artists who fixed toilets but never got famous, and who did it anyway."

This is an immensely comforting sentence.

At 73 I'm finally comfortable with not having an answer to "Why do you write?" other than: "Because I am a writer." Period.

There is no other reason.

What an amazing story, Henrik!! Yes, the compulsion to create is real, whether someone likes it, reads it, appreciates it or not. The compulsion to be free, that's what it really is.

What an incredible thing, also, to find this story where you live. There were people on that island just like you, so inspiring.

I dream of a retreat of people just like us IRL - dead and alive :))

Thank you for writing! Best regards from Stockholm!