The paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, I change

Looking for Alice, part 4

Almost three years ago, I wrote an essay, called “Looking for Alice,” about how I met my wife Johanna. This is a prequel of sorts. See also: part 2 and part 3 of the series.

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.

—Carl Rogers

On various hard drives and USB sticks stored in our barn, I keep the diaries from my university years, 2010–2014. Last week I reread them for the first time since I wrote them. It was interesting, but also uncomfortable, to see myself at such a distance. Many of the things that were important to me then are not visible from here (I only see blurry outlines of the situations I was in and what I thought), while other things, which I couldn’t see at all then, stand out clearly now. It’s like when you zoom in on a graph, you mostly see the small daily fluctuations, while when you zoom out, you see the trend.

I spend page after page interpreting the nuances of the situations I’m in, without seeing that the situations all resemble one another and follow each other with an almost mechanical logic.

For example, I often feel miserable. (This is partly an illusion created by the fact that I wrote more in my diary when I felt agitated, so it wasn’t quite as bad as it looks, but I really did feel down a lot back then.) I was worryingly often sick: there were five hospital visits in 2012 alone. I also had much more angst than I realized. The angst I was aware of and wrote about was only a small part, the most intense part. I don’t seem to have understood that many other things I experienced were also signs of anxiety—my ceaseless work, my desperate need to always be around people, my fatigue, my feelings of unreality, the moments I would wake in the middle of the night, realizing that I would die.

And every time I’m miserable in the diary, I know what will happen on the next page: I will throw myself into some activity that can distract me from myself. It is like clockwork. As soon as I feel bad, I get busy, I seek out social situations where I feel high status (the literary world), I go to parties, get drunk, and/or flirt with people. A wave of euphoria breaks over me, and the anxiety disappears—and then I overstep my own boundaries and do things that fill me with shame. I’m back where I started. The loop starts over.

I was almost completely trapped in this holding pattern, like a plane circling for years above the airport, waiting for clearance to land. I couldn’t acknowledge what was happening.

From September 11 to 13, 2012, I sleep at my friend’s place (ten minutes from my apartment), and when I leave on the 13th, it seems I can’t bear to go home, so after a lecture on macroeconomics I tag along to a party and don’t make it home until the 16th: this was a fairly typical week for me during this period. I was never alone, except when I was laid up with a fever. A recurring theme in the diary is long, Cărtărescu-inspired accounts of fever dreams filled with disturbing bodily textures. One of these reports is from February 2013, and it is clear that I was writing it in a bar where I read for class: I was still sick, but as soon as I could get out of bed, I had to look for something exciting that would distract me from my feelings.

It’s almost as if my need to be happy led me into misery. But that’s not really it.

Rather, it’s more like there are two kinds of happiness in the diary. I also felt very happy when I read, for instance, and there was nothing destructive about that happiness. Reading didn’t trap me in loops, it carried me forward and inward, toward myself. I really read a lot back then, fifty books a year on top of course literature (and the books were good, too: Pascal’s Pensées, Augustine’s Confessions, the collected works of Coetzee, Tranströmer, Sebald, Sem-Sandberg, Popper, to name a few), and I get a lovely feeling when I read my book notes. I also like the passages about my travels (I somehow managed to visit seventeen countries during my four years at university), and it amuses me to read about the creative projects I was working on. The happiness there feels entirely different, much softer. There is none of that jaggedness and intensity that characterize the joy I felt when I thought that people were attracted to me, or when I was on stage in a bar reciting poems, or when I drank. The joy of reading and travel was more like a cocoon. I hid and changed.

Such was the joy when I started to get to know Johanna, too, in the fall of 2011.

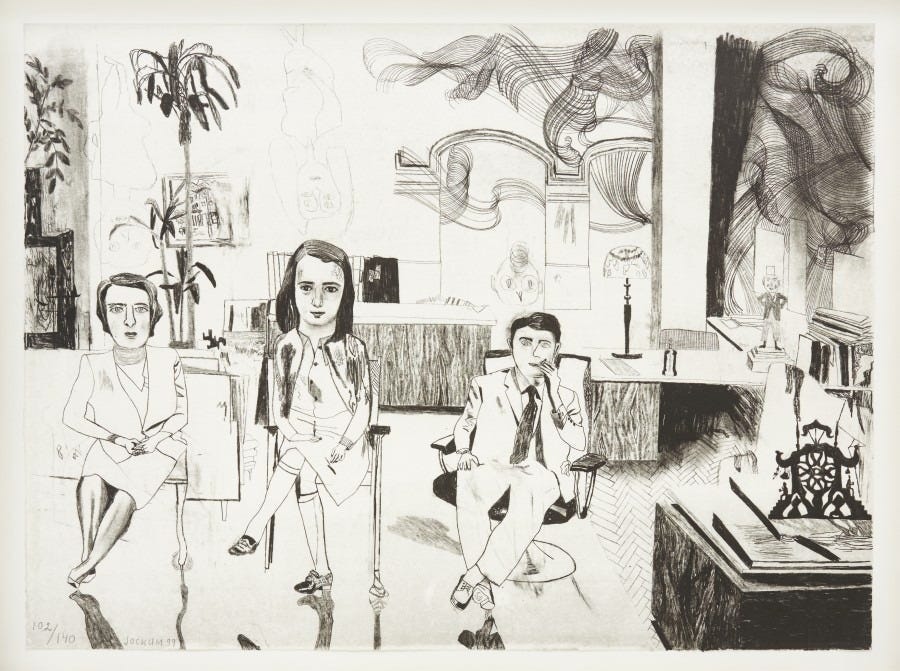

A few nights ago Johanna showed me an old TV broadcast about Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström (two Swedish artists who used to be married), and I suddenly remembered how I perceived Johanna before we became a couple. What struck me in the documentary was that there was nothing performative about Mamma and Jockum (unlike most artists I’ve worked with).

In the late 80s, while still in art school, they had kids together, and so have spent almost their entire adult lives inside the bubble that is their apartment and studios. They haven’t let themselves get polished by social life, which makes them seem odd in the way very young children seem odd when they think aloud. In 2005, Jockum is in NYC to open The Armory Show, where he’s the headliner, and he really doesn’t fit in among the other artists. He looks like a roe deer that has strayed into the gallery, sniffing at things. How they come across to others genuinely doesn’t seem to matter to Jockum and Mamma; they just want to crawl around on the floor of their studios, painting, working.

That’s how Johanna struck me, too, when I ran into her in the frozen section of the supermarket, at the bookstore, or in the street. She seemed her own in a way that I was not, and she seemed to be close to life. I remember seeing her outside of the pharmacy, where she sat eating at a small children’s table, throwing her head back in laughter as her friend read aloud from Sara Lidman’s The Tar Pit. I remember the intensity with which she listened and the unpredictability of her questions. I had talked to her for only ten minutes when I fell for her. It didn’t matter that she turned me down when I asked her if she wanted to do something someday—that a person like her could even exist was enough to make me feel that the world was a good place.

So I notice two kinds of happiness in the diary: a soft joy, which makes me ease up and feel more like myself, and a hard one that again and again leads me into shame.

There is another difference between these two kinds of happiness. The soft one is private—I struggle to share it with others—whereas the one that drives me into misery is social. For instance, at university I could never bring myself to ask librarians for help finding the books I was looking for—it was way too private for me to reveal that I liked to read Jean Rhys, or Imre Kertész. But in other situations I was totally shameless about telling people private stuff they probably didn’t want to know! There are several passages where “attractive people” are drawn to me (and when I write “attractive,” I mean people I assume other people are attracted to), and when that happens I get excited in a sharp-edged and feverish way. This happiness I have to share. I want to force it upon people. I’m ashamed but I can’t stop myself: the excitement, it seems, comes from being seen as the sort of person that this or that person desires. I don’t actually seem to like going home with them; that part makes me uncomfortable. But I get worked up by the thought of telling people about it.

Conversely, when Johanna after 18 months finally asks me out (and I feel that other kind of joy—the one that tells me that she is a path towards life), then I don’t want to talk about it. My friends ask about her, they are curious, but I avoid the subject. I get defensive. What Johanna and I have is too private. I’m afraid that they will misunderstand our relationship or reduce her to one of their stereotypes. So I hide myself from them.

All of this makes me very sad when I read the diaries. That I couldn’t show who I was, that I treated people in ways they didn’t deserve, that I lashed myself so hard about treating people in ways they didn’t deserve, that the self-flagellation drove me back into the loop...

If I jump forward two years in the diary, the pattern is gone. I have broken out of the loop and am moving forward. What changed? I’m not sure. It is hard to tease out these things: a life is a complex pattern.

But the main thing was, surely, Johanna. I remember the first time she invited herself to my apartment, how we sat on the balcony, and how I suddenly heard myself say things I had never been able to say before, not even to myself. I felt no shame when she listened. It was, among other things, because of her eyes. What made them light up was the complete and utter opposite of what made the eyes of others light up: if I talked about things that normally earned me admiration, she got bored, but when I spoke about what was private, odd, embarrassing, painful, or taboo, she became curious.

She was moved by reasons in a way that no one else I knew was. She seemed incapable of accepting as true anything she hadn’t deeply considered herself. Her default position was, “I don’t know.” But if she received information that contradicted her, she eagerly changed her mind. And she treated me as if I lived by that standard, too.

It was a strange mix of relief and discomfort to meet a person who loved me in the Erich Fromm sense (“I want the loved person to grow and unfold for his own sake, and in his own ways, and not for the purpose of serving me.”) A relief because it was like decompression to let go of all of the fear and insecurity that made me shape myself for approval, and to feel my own sense of curiosity and value unfold. But discomfort because it put me on a collision course with the life I had been living and many of the people I interacted with. When I understood my values, I had to confront the pain of looking stupid and having people get angry at me when they disagreed with my decisions; I had to let go of the safety of social status and the coping mechanisms I had relied on. I soon withdrew from oversocializing, stopped giving poetry readings and publishing in magazines, and instead turned toward what felt private and alive.

At this point the diary gradually shifts from being a place where I vent my feelings and make laconic jokes about my flaws to a place where I think about things that interest me or give me awe. To use Visa’s phrase, I began to focus on what I wanted to see more of. I moved toward the good, rather than away from the bad.

In the late winter of 2015, 18 months after Johanna and I started dating, we bought a house in the countryside near my grandparents. By this point we were 25. We barely used the internet from then on and spent our days reading and talking. We gleefully questioned everything we had learned and tried to figure out how it would make sense for us to live. On the weekends Johanna and I walked with my grandfather along the paths he’d made around the tarns, asking him about his life. He had always been my big role model as a kid because of his kindness and strength of character. It was fantastic to have a friend like that to share life with.

At our house and at my grandparents’s, the norms and expectations were completely different from what they had been in the city—everything felt richer and more human here. The thought of living transgressively, the way I had during my years at university, was now foreign to me.

I was no longer reacting to what happened in mechanical ways, but was moving forward, toward things that mattered to me. It felt like being set free.

Acknowledgements

As always, this essay is the result of many conversations with Johanna Karlsson. The writing was made possible by the generous support of the paying subscribers—thank you! Esha Rana did the copy edits.

The drawings and paintings used in the essay are, in order:

Tête d’homme, Alberto Giacometti, 1961

Dagen efter, Mamma Andersson, 2020

Vi bor på kontoret, Jockum Nordström, 1999

Reading this, I'm starting to think Escaping Flatland is a bundle of love letters to Johanna. 🤭

It is always a boon to my mood, my day, my week, my life, when I give myself the time to sit down and read your writing, Henrik. Thank you for writing about the personal, and the personally interesting.