On feeling connected

generosity is potency

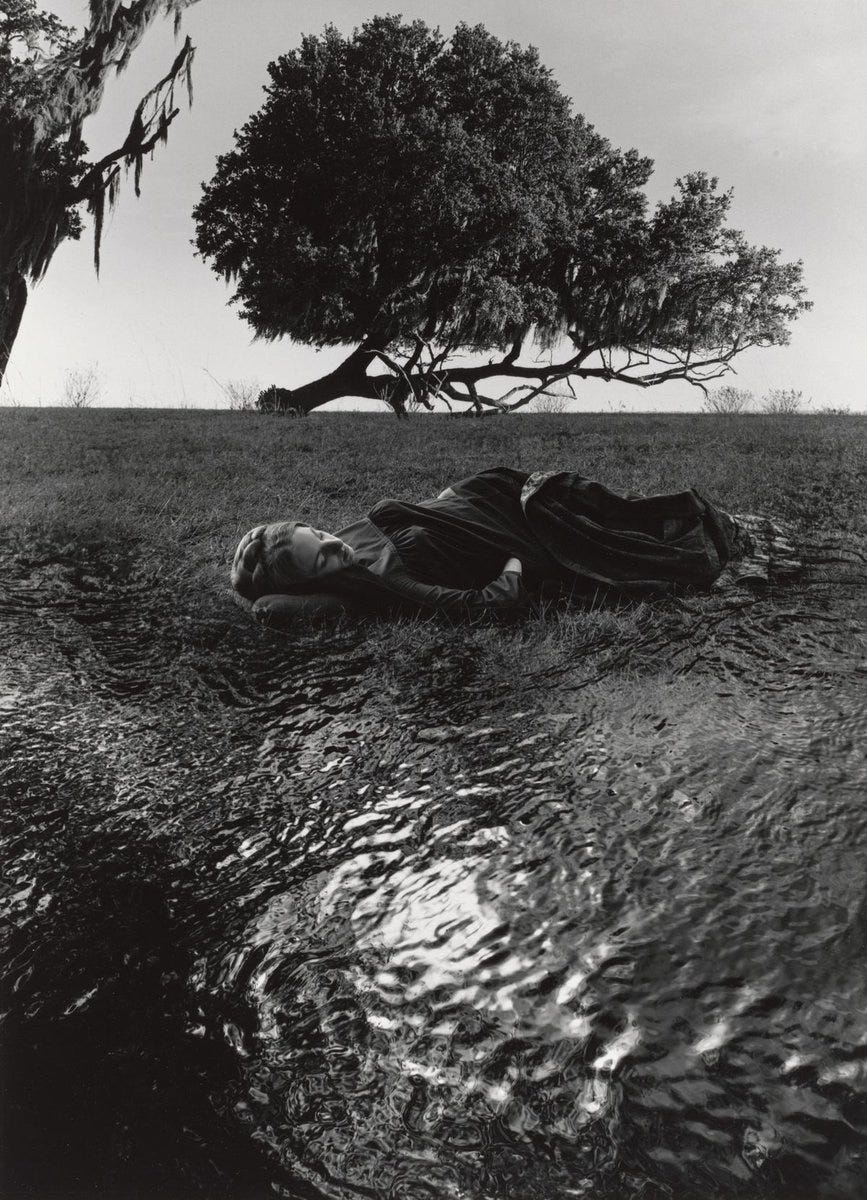

Jerry Uelsmann, Untitled, 1966

An earlier version of this post was published on the waste book on September 5.

Erich Fromm makes a useful observation in The Art of Loving when he talks about what it means to give. He says that many people think of giving as giving up: you have less than you had before. He calls people like this “unproductive.” They only give if they think they can receive a favor in return.

Then there are people who are actually generous—they are committed to serving others. But they see it as a sacrifice: it is painful to give, and this pain is, in a sense, what makes it valuable. “I will give of my time and energy and potential so that my baby can grow. Shouldering responsibility makes my life feel meaningful, and I want it to be hard at times; that makes me feel good about myself.”

I’m basically quoting myself here; I often think about giving in this way. And seeing giving as a sacrifice is a step up from the full zero-sum thinking of the “unproductive.” But there is a deeper level still: people who think of giving as an act of potency.

When I give of myself, when I genuinely care about others, I generate a feeling of connection, a feeling that is closely related to love. This is a feeling we long for. And it is common to think of it as something we must receive—that to feel a connection, we must find someone who sees us and who cares about our authentic self. But what people who see giving as an act of potency realize is that this feeling of a loving connection is something you can produce yourself. If a feeling of connection to the world and other people is a kind of wealth, it is a wealth you don’t need to inherit or earn. It is more like you are the federal reserve and you can just print that stuff.

Look at people on the train and remind yourself that they have an entire world inside their head—and feel how a sense of connection flows from you. You can do this with animals, too, and plants, and objects, and ideas. Pay attention to things as if they are too big to fit in your head—and feel love seep out of you. Do small acts of kindness and don’t take credit. Care more than necessary.

Notice that when I talk about giving, I'm not talking about twisting yourself to please others, or making yourself prey for people who exploit the meek; I'm talking about giving from a deep and spontaneous place inside of you.

Giving in this way, “I experience my strength, my wealth, my power,” writes Fromm. “This experience of vitality and potency fills me with joy. I experience myself as overflowing, spending, alive, hence as joyous.”

It is a nice little mental trick.

But it is more than that. Because at some point, sooner than you would wish, life will turn into a catastrophe. People you love will die. You will get chronically ill. There will be violence. And at that point, you might not make it unless you can generate this kind of generous love that connects you to the world and gives it meaning. Frankl and Antonovsky both made this observation about concentration camps. Prisoners who had nothing beyond themselves to live for didn’t live. We see this in everyday trauma, too: people who are unable to reach beyond themselves to find meaning have to turn to more destructive coping mechanisms to handle the pain life throws at them. They chase achievements, they overwork, they form addictions, they act out, they fall into depression. When you look at how these coping mechanisms wear a person down over decades, as in the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the difference between these self-centered coping mechanisms and the potent-generous ones is jarring.

This essay is an appendix to the series made up of “Looking for Alice,” “Dostoevsky as lover,” and “Relationships are coevolutionary loops.” It is also related to “Seeing people clearly” and “Two kinds of introspection.”

When people are blind to this mode of giving, it also makes them worse at receiving it - if giving is always loss or sacrifice, then they don't want to accept the gift and cause that loss to the giver. They aren't able to conceive that giving the gift is its own reward, and thus refusing the gift is denying the reward to the giver.

Suggests that being good at receiving is just as important to finding connection as being good at giving.

(Inspired by my other comment, but felt like this deserved its own thread)

“Excellence is an art won by training and habituation. We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.”

– Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy (1926)

Love this short piece it fits well with the aristotelian idea that you should give because a Giver is the type of person you want to embody.