Agentic fragments

Highlights from the cutting room floor, vol. 6

I once gave my grandfather a compliment on a knitted sweater he was wearing, only to have my grandmother loosen a thread and unravel the whole thing. “He’s getting too thin for it,” she said. The next time I visited, she had knitted the thread into a sweater my size.

They had both grown up on small farms, in the days before electricity, and began working as children. They farmed, slaughtered, built houses and roads, sewed the clothes for their four children, wired the electricity. Their way of appropriating the world was fundamentally different from mine: everything around them was something they could take apart and put back together. If they didn’t like how the light fell in their living room, they moved the windows. If they needed a lathe, they disassembled a hammer drill and turned it into a lathe. Their world was filled with affordances that I didn’t see. Where I saw a sweater, she saw a thread temporarily shaped as one—it could just as well be a scarf, a pair of socks, a hat, or six gloves. She saw more degrees of freedom than I did, and acted on it.

This capacity to see through objects and notice how they can be reconfigured is closely related to agency. Having learned how to pick things apart and build them back together, my grandparents had a more granular view of the world. They could tinker with and adapt the world around them to better fit their needs. They were, in their circumscribed world, much freer than I was: no matter what they wanted to achieve, they could nearly always find a path.

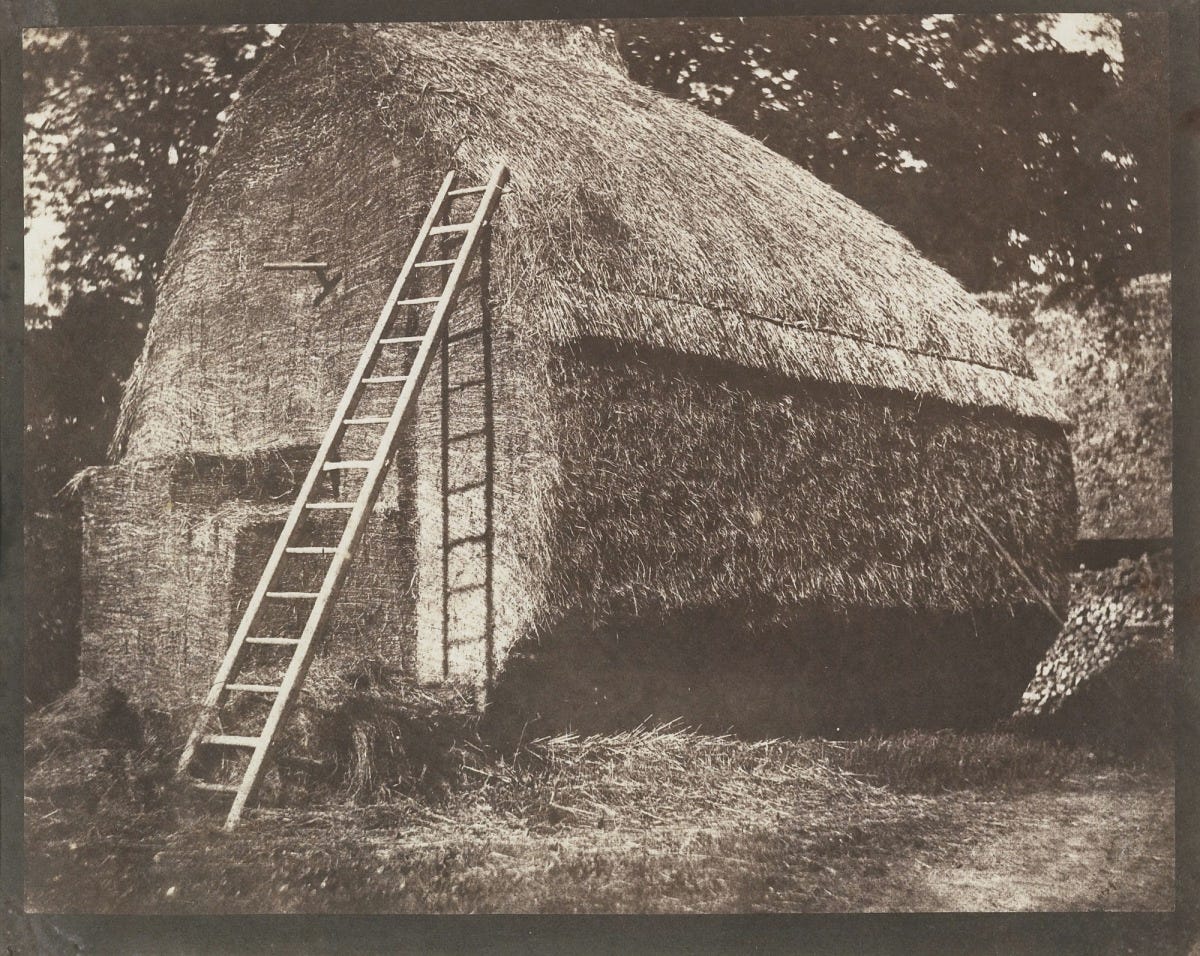

Despite growing up in poverty, my grandparents and the people of their milieu could do grandiose things. A miner lived next door to my grandmother when she grew up. He was a silent, brooding man and spent his spare time locked up in his barn. This had been going on for 25 years when, one day, during the harvest, when my grandmother was seven, a bellowing sound arose from the barn. He had built a full-size church organ.1

In July, Johanna Karlsson and I wrote an essay about agency, which we defined as a combination of autonomy and efficacy—the capacity to form independent goals and manipulate the world around you dextrously enough to get it done. During that project, we ended up with nearly 20,000 words, of which 16,000 were cut in the final draft.

Hopefully, we’ll get around to finishing a few more essays on the topic, but in the meantime, I wanted to share some excerpts from the full draft.

At the end of today’s post, there is also a collection of links to essays and films I’ve been struck by recently. For previous fragment collections, see here, here, here, and here.