When facing a complicated problem, don't try to solve it, try to understand it

I wrote this essay with Johanna Karlsson, so it is a collaboration but I narrate. /Henrik

Every problem cries in its own language

Go like a blood hound where the truth has trampled

—Tomas Tranströmer, “About History”

1.

Like most people, I was really bad at making decisions when I was 25. If I was confronted with a complicated problem, like figuring out what to do with my life, I would pick a solution on a whim, more or less, or, if that was too hard, I would straightforwardly just ignore the problem. This made my life feel less than good at times. But then something fell in place.

Or no, it wasn’t a specific moment like that. It was more the cumulative effect of spending 36 years trying things and failing and learning a little bit here and there, and—mostly over the last four and a half years—having a few conceptual breakthroughs. Most of the insights, interestingly, came after my wife Johanna decided to turn the derelict grounds around our house into a garden. Ambitious gardening, as it turns out, is a good way to get better at dealing with messy problems.

Let me tell you about that and the core thing I learned.

So, in 2021, when our oldest daughter Maud was four and Johanna was pregnant with Rebecka, we bought an old farm on an island in the Baltic Sea. We were able to get it cheaply because there was a glorious total of one single room that could be heated in winter. Also, a large swarm of false spirea shrubs was pushing right up against the house (they were even growing inside the walls, we later discovered—ghostly white trees with leaves like paper; don’t even get me started).

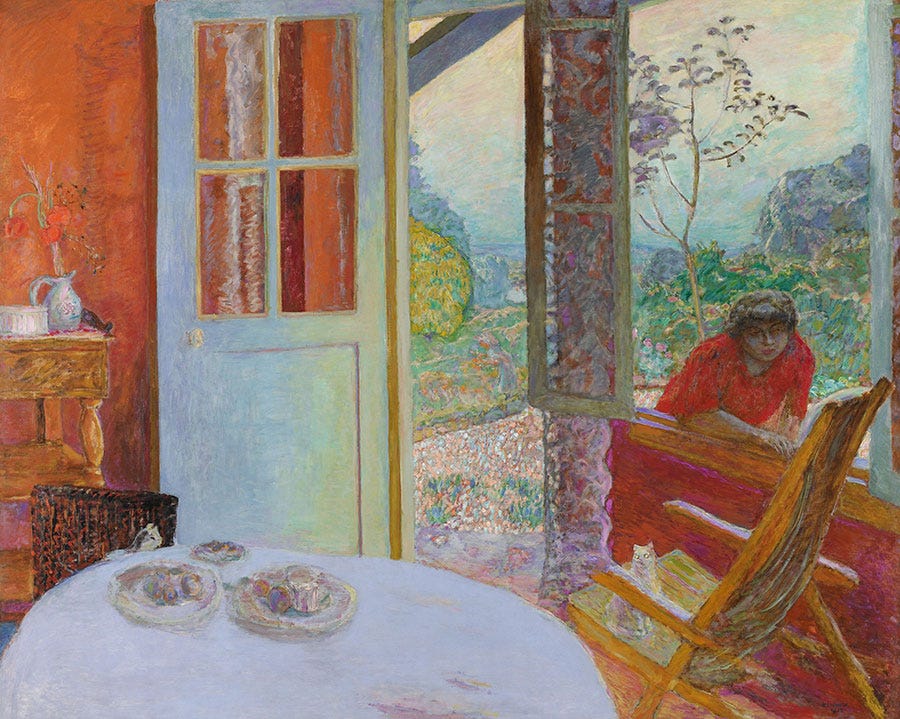

Anyway, it was while removing the tennis-court-sized section of shrubs closest to the house that Johanna got the feeling that this place, despite its appearances, was actually meant to be a great garden. Under the overgrowth, we uncovered stone walls and beautiful differences in elevation with views into the forest, where evening light striped the ground with the shadows of maples and oaks. It was like when you get half an idea for an essay and just know that this thing could turn into something deep and moving if you pour everything you have into it.

The more Johanna thought about it, the more she felt like she couldn’t just plop some flowers down here; she got obsessed with the idea of making a great garden, one that really took full advantage of the landscape. But since she knew nothing about gardening, she had to learn everything from scratch.

And as it turns out, making a great garden (as compared to a good one) is a remarkably complicated project. With so many interconnected parts and considerations, the project would force her to go deep on learning about process and problem-solving.

When Johanna began looking into it, one of the questions she steered toward was how great garden designers, like Dan Pearson or Miranda Brooks, evolve their designs. What is it they do differently from the garden designers that make gardens that are merely good?

Skimming course literature and gardening books to get a sense for the field, Johanna learned about the more obvious things that can go wrong, like planting flowers that need a lot of sun in the shade, or making the garden too high-maintenance for your time budget. But when it came to figuring out how to make a garden look exceptionally right, there wasn’t much to be learned from the handbooks. The books would present tools and techniques you could use (pointing out, for instance, that it is good to work with contrast), but these techniques were used by both ok designers and great ones; the difference was that the great designers always seemed to pick precisely the right kind of contrast in the right place and the ok ones didn’t. And the question was, how do you do that? What did the great designers see that the good ones didn’t? And how can you learn to see it too?

2.

As a gardener you have to stay on top of an awful lot of things.

—David Lynch

I remember discussing these questions a lot with Johanna and pooling our thoughts—I come up against similar problems every time I’m writing an essay. Faced with endless options, as you are when planning a garden, or writing an essay, or shaping a life, how do you reliably figure out what the right solution is?

I was somewhat happy conceding it was a mystery. Sometimes things turn out well and sometimes not. But Johanna has a lot of what Laura Deming calls the rage of research (“But why????? my brain will scream.”). She absolutely cannot tolerate it when she doesn’t understand something.

So when Rebecka was a baby and only wanted to sleep if her mother was next to her in bed, Johanna filled the bed with books, work notes, and lectures of designers she admired. Studying their processes, she learned many useful things. But it was all a blur of small decisions. She couldn’t discern the underlying pattern of why they chose one thing over another, or how they reached their conclusions.

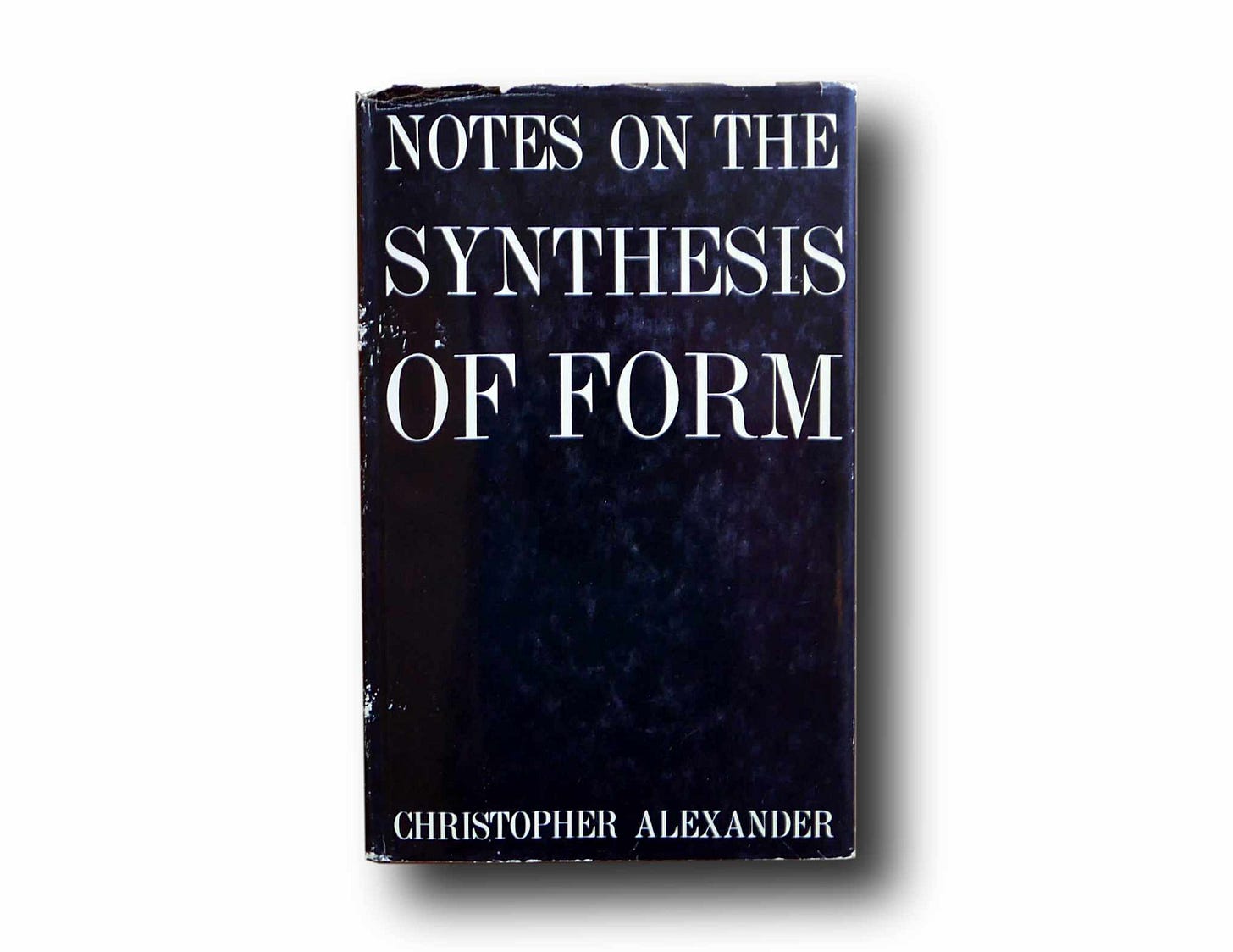

Until one day, she found a skeleton key. She figured out what they were doing. This insight—which took form during a close reading of the work of the design theoretician Christopher Alexander—was so basic and general that it also helped us figure out how to write better essays and deal with all of the complex, messy problems that we keep bringing on ourselves by acting on our curiosities and convictions.

Compressed to a single paragraph, the core idea was this:

When faced with a difficult problem, don’t try to solve it. Instead, make sure you understand it. If you understand it properly, the solution will be obvious.

This idea has been expressed by many people (the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck comes to mind, as does Einstein), but to me the clearest and most useful articulation of the underlying logic comes from Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form.

It was in Notes in 1964 that Alexander introduced his now-famous idea of form-context-fit. These days, I mostly see it referenced in the phrase product-market-fit—meaning you’ve found a product that consumers are hungry to pay for—but it was originally a broader, deeper, and more interesting idea. Alexander proposed form-context-fit as a way to objectively judge if a design is good. Or, to phrase it differently, form-context-fit is a way for us to judge if a specific solution to a problem is good. And what Alexander said was that a design is good if and only if the form (of the solution) fits the context (of the problem).

Let me illustrate this with a simple example: say you’re buying clothes. Here’s a common way people approach this problem. They go to the store and see a t-shirt with a print on it that they like (perhaps it is a picture of Jimi Hendrix and underneath the picture it says, “Bob Marley”), so they buy that. Or they see someone look good in a pair of white linen pants and go find a pair for themselves. But then, when they come home, they discover that it doesn’t fit with any of the other clothes they have, so it gets hidden at the back of the wardrobe. In this example, the clothes that get bought are the form, and they fail because they do not fit the context (which is made up of, among other things, the rest of the wardrobe).

So what should you do? Well, here’s the useful thing about Alexander’s definition of good design as design that fits the context: it tells us where we should look if we want to find a proper solution to the problem.

We should look at the context.

Let’s stay with the clothes shopping example. What people who are good at picking clothes tend to do, among other things, is that they think in terms of outfits, not individual pieces of clothing. “If you have some clothes you wear a lot, you should buy things that make them look better.” Also, good clothes buyers think about what situations they are going to be wearing the clothes in. “You need lots of clothes for everyday life, and you don’t, normally, need as many fancy going-out clothes.”

In other words, people who are good at buying clothes seek to understand the context that the clothes are going to be in (the shape of the body, skin color, the full outfit, the budget, and so on), and then they buy things that plug the holes they have in their wardrobe.

This is how you arrive at a good solution.

3.

Looking again at the work of great garden designers, Johanna noticed that the flurry of activity that she had seen was, in fact, a systematic probing of the context. The designers were taking actions aimed at uncovering the context bit by bit, until they had figured out what the garden needed to be.

With this in mind, Johanna looked at our own garden anew. She began articulating what was important about the context. There was a very strong atmosphere in the landscape that came from the surrounding woods and meadows, as well as a certain moodiness that comes from the old moss-covered dry stone walls. Whatever we introduced in the garden couldn’t disturb this atmosphere, or break it up.

It was this sense of place that we needed to protect. Any mark made on the land would have to be made with a sensitive hand to maintain the mood here. The walls and the land spoke for themselves [...] it was clear that there was not just one mood here—each corner had its own atmosphere. We would have to unpick this place stitch by stitch to know how to put it together again.

—Dan Pearson

And it wasn’t enough to respect the context. What we put in needed to make the already-existing stronger. This also applied to the other aspects of the context, the architecture, the ecology… And it applied to the part of the context that was us—the garden should make us feel more alive and encourage us to engage in the activities we want to engage in. The next thing we put in needed to make the previous things stronger.

As the context came into focus, it became clear what needed to be done.

To refine the atmosphere of the garden, we realized that we needed to get rid of a hedge of hydrangea bushes that the former owner had planted, since their pastel blue had an intense, screaming quality that clashed with the moodiness of the landscape. Getting rid of this would strengthen the wholeness of the place.

So Johanna and the kids took two days to cut and dig the bushes away (the eight-year-old helping, the four-year-old mostly digging for mice), and with the hedge gone, the context flooded us with new information. We’d been confused about what to do with this part of the garden, which is a rather weird rectangular enclosed space, probably an old animal enclosure, with a confusing mood; but with the hedge gone, and the atmosphere thus more coherent, we could see what would pull the landscape in the right direction: a parterre, like the one at Rousham.

The parterre at Rousham gardens, by Andrew Montgomery, House & garden

Finding form-context-fit is like solving a Sudoku. To figure out which number should go into a square, you look at the other numbers in the same row—it can’t be one of those numbers; that’s one constraint. Then you look at the numbers in the same box; it can’t be one of those either. Once you’ve figured out all the numbers that are not allowed, you know the constraints, the context.

You also know what the solution is.

In most situations, there are a near infinite number of potential answers, yet only a few that are good. Luckily, each constraint that you map reduces the search space, making it easier to see what the right answer is.

If you map the context well enough, the solution will reveal itself.

4.

When I was younger and felt lost and alienated by life, I was always stretching for a solution, something that could get me out of my predicament. I applied to university, I switched majors, I started companies. But I wasn’t paying attention to the context. I didn’t see who I was or how the world works, and it didn’t strike me that I could map this systematically. So my solutions never fit.

Now that I see the landscape more clearly, I can see that I was standing inches from good solutions to many of my problems for years before I saw them. (It is unnerving to observe someone being so close and yet so far away.) I was too stuck in my head, too stressed about finding a solution to see what was in front of me, too narrow-minded to see the gradient I had to follow.

I often got fixated on a solution before I’d actually understood the details of the problem. This is a common and strong human tendency: to distort our understanding of the problem to make our preconceived solution look like the right answer. Obviously, this makes it harder to see what the right solution is. You won’t be as attentive to the landscape if you hide your face behind a badly drawn map.

But when I think in terms of understanding the problem, or mapping the context, rather than solving it, I’m put in a state of mind that makes it easier for me to get it right. Being curious about the problem counteracts my confirmation bias and helps me see through to the deeper layers of the context where the better solutions hide.

How to do this, practically speaking, will be the topic of the next part, which we hope to finish in the next few weeks.

As always, a big thank you to the paying subscribers who fund our work. We wouldn’t have been able to keep going for so long without you. If you want to support Escaping Flatland, we are not yet fully funded. /Henrik and Johanna

This is a deep insight disguised as an everyday observation about shopping or gardening.

How do quantum computers solve problems? How do quantum elements in plants solve optimization problems in photosynthesis? It is about maintaining coherence so that all solutions can be explored and the right one left standing at decoherence.

I think the mental state of openness to context you suggest is a version of this -- staying open to all possibilities until an attractor draws us to the solution. Your piece inspires me to write more about this.

I can’t walk by a box hedge without dreaming of how to create a parterre like those in the Rousham Gardens somewhere in our yard. As the context of our lives shifts so does the idea of the possible form of our gardens.

Your essay though made me think of the context of making art and the form it takes when I consider trying to make it fit a market. What if I just didn’t consider market fit? What if I made art to fit the context of my life alone? Would that make my art “better”, so much so that a market I can’t conceive emerges? I wonder. Your comment in July that writing few essays per year would be an ideal, but you can’t imagine anyone funding that project runs similar lines. Van Gogh sold one painting in his lifetime. One. And yet what he created now resonates with so many people, and that a market emerged for his work is undeniable. He just didn’t see it happen. I want to explore the personal context for art and what success (or the perfect solution) to making it looks like given what your essay makes me think about “form fits context”. Thanks.