On the pleasure of reading private notebooks

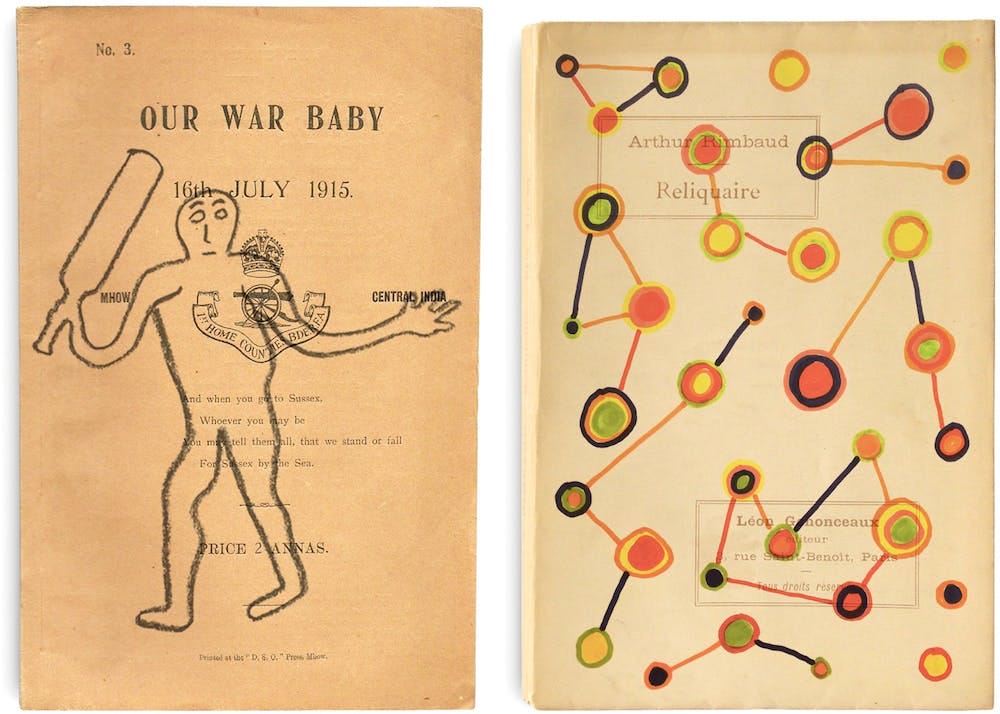

Roy Gold, Our War Baby and Arthur Rimbaud’s Reliquaire

An earlier version of this was published in the waste book on January, 25, 2025

A surprising number of my favorite books were not meant to be published. They were private notebooks, or fragments from works-in-progress that never got finished: among them Pascal’s Pensées, Simone Weil’s private essays, Lichtenberg’s waste books, Herzog’s Conquest of the Useless, Kafka’s diary, Joubert’s Carnets, Wittgenstein’s Brown and Blue Notebooks, and Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book.

One reason I like this genre is that people censor themselves less when they are writing in private. I don’t mean that they are saying things that would get them ostracized in print (though that happens). I mean uncensored more generally: they allow their mind to be as it is on the page, however odd their thoughts are and however random the connections between them. They are not second-guessing if their thoughts are interesting to others, or trying to frame them in a certain way.

And, paradoxically enough, this is more interesting to read. Lichtenberg wrote a note about this in his private waste book (posthumously published 1800–06):

An alert thinker will often find more that is instructive and delightful in the playful writings1 of great men than in their serious works. The formal, conventional, ceremonial is usually omitted from them; it is amazing how much wretched conventional stuff still appears in our way of narrating in print. Most writers put on airs, just like many people when they are having their portraits painted.

For a more contemporary example of a similar phenomenon, Michael Nielsen says that the old bookmarking website del.icio.us had a “network” feature that

(a) hardly anyone knew about; (b) let you follow other people; but ( c) because no one knew, people just bookmarked unconsciously what they were really interested in. It was so much more interesting than twitter etc…

I think this is because our genuine thoughts (and interests) are more detailed and alive than the simulations we have of what we should say (or be interested in). When we think no one listens, we relax into the genuine. I’ve been told, repeatedly, that I hide my most interesting thoughts in the footnotes.2

Browsing through private notes feels more like participating in a happening than reading a piece of literature: this is what happened, more or less in real time, inside another human. Their beauty has more in common with the beauty of nature than the beauty of art. It is sprawling, strange, tangled, and confusing—but the overall work has a deep structure to it that art can’t imitate. It is not the result of a plan, but a generative process. I’m reminded of being in a pine forest, surrounded by large beings that stretch up from the ground.

Another thing that attracts me to private notes is how they talk at two levels. There is the content and then there is what Schopenhaur called the style, namely how a particular mind processed the content. All writing operates at both levels (and published works often deal with the content in a more systematic way3), but the style comes through more strongly in private notes.

In published works, the style is nearly always somewhat fake and didactic—there might be rhetorical questions and so on to give the impression that the writer is thinking on the page, but really it is all arranged and tidied up, with all the false starts cut. Instead of tentative definitions that the writer probes and refines, you just get the final thought, where all the reasoning steps are baked in, hidden. It is a simulacrum of thought. But in the private notes, you get the trembling, confused, groping real thing45—and even if the writer arrives at nothing, there is something intimate about seeing how another person thinks.

If the writer is intelligent, original, or sensitive, it is also highly instructive: to see how Kafka, when he is dissatisfied with a story, doesn’t edit it, but starts over from scratch with the same prompt and goes off in a new direction; how Ingmar Bergman scribbles in his work book, again and again, versions of this line: “(I will write as I feel and as my people want. Not what outer reality demands.)”; or how Darwin collects unprocessed observations for years before a theory arises, and how he keeps special track of everything that confuses and contradicts him, since he knows that he forgets those facts faster than average.

In the 1980s, before he went into hiding, the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck began writing his research in the form of diaries. Pursuing Stacks is a 600-page-long manuscript on category theory, homotopy theory, and algebraic topology, containing letters, diary notes, and also some remarks about the birthday of Grothendieck’s grandson.

In Récoltes et Semailles, a 1,500-page-long autobiography meant as a preface to Pursuing Stacks, Grothendieck explained the decision to do mathematical research in this diaristic way:

[I wanted it to] read rather like a “travel log”, in which the work is carried day after day, in plain sight and as it is actually happening, including all the mistakes and mess-ups, the frequent look-backs as well as the sudden leaps forward [...]

It is this part of the work which, albeit puny looking - not to say (often) harebrained - is often the most delicate and essential part of the process: it is truly there that something new becomes manifest, through intense attention, solicitude, and respect towards the fragile and infinitely delicate thing about to be born. It is the most creative part of all - that of conception and slow gestation within the warm shadows of the maternal womb ... [It is] stupefying once one stops to think about it: namely, that this “most creative part of all” within a work of discovery [...] is reflected almost nowhere [...]in textbooks and other texts of a didactic nature, in articles and original memoirs, as well as in oral lectures, seminary presentations, etc. It is as if there existed, for what seems like millennia, tracing back to the very origins of mathematics and of other arts and sciences, a sort of “conspiracy of silence” surrounding these “unspeakable labors” which precede the birth of each new idea . . .

This is, I think, at the root of why I like reading private notes so much. There are so few places where we get to be close to other people and see the messy humanity they carry behind the identities they have polished for society life. There are so few places where we can apprentice ourselves to the unspeakable labors of thinking and feeling that precede the birth of a rich inner life. But here, we can.

Acknowledgements

Thank you, Esha Rana and Michael Nielsen for discussions and feedback.

“Playful writings” can be interpreted as published works of a playful character, but I do not think that is what Lichtenberg has in mind, given the rest of the passage. Also, the German phrase that has been translated as “playful writings” is “Spielen großer Männer”—literally, games of great men. I take this to mean, primarily, notebooks, letters, and aphorisms.

The stuff that ends up in the footnotes is usually messier and more uncertain than what ends up in the main text. I’m groping around and can’t really get it right, but . . . it has something and I don’t want to delete it, so into the footnotes it goes. But it is really fun to see someone thinking at the edge of what they are capable of thinking! Maybe I should have a blog that is only footnotes.

The good thing about publishing (at least if it is done with a demanding audience in mind) is that it forces the writer to clean up their thinking, notice holes in the reasoning, and, generally, raise their standards. It is like how my house, for some reason, is only ever really clean when I have visitors. So, there are downsides to private notes, when it comes to thoroughness, completeness, and standards.

I’m reminded here of the Feynman interview where Weiner says that it is a shame that we can’t record what was going on in his mind when he was making his discoveries, that all we have are these scraps of paper with his notes and calculations.

Feynman:

I actually did the work on the paper.

Weiner:

Thats right. It wasn’t a record of what you had done but it is the work.

Feynman:

It’s the doing it — it’s the scrap paper.

Weiner:

Well, the work was done in your head but the record of it is still here.

Feynman:

No, it’s not a record, not really, it’s working. You have to work on paper and this is the paper. OK?

Not everyone thinks on the page like this. As Hadamard writes about in The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field, most strong mathematicians seem to think pre-linguistically in their heads and only use the paper to check their reasoning and craft relay results. But to read the notes of those who do think on the page is instructive.

The messiness and ambiguity of private notes makes them fun to read alongside LLMs, by the way: by feeding confusing or meandering parts to an LLM, I can often get the padding and explanations I needed to make sense of what happens and turn the thoughts into a form that is more ergonomic for my mind. Perhaps the future of writing is to publish more of this kind of gnomic private writing, where you write as densely and as personally as possible. Readers can then use it as out-of-distribution data to seed AI systems to get into interesting thought spaces. I think Venkatesh Rao has written about this possibility somewhere.

i like ur footnote idea of a post that consists fully of footnotes

Loved this! I was just thinking this morning about how much I enjoyed reading the journals of Jan Morris, John Cheever, Susan Sontag, Anais Nin etc. It's always such an interesting mix of confessional and workshop, with the added pleasure of knowing they weren't written to be performative. In my personal journal, I wrote down that they all "start from fog and not from clarity", and I think that about captures the essence of what makes them so meaningful, especially to other craftspeople.