Being creative requires taking risks

When children learn to draw, they tend to make more and more interesting images for several years until around age five, when they learn to be boring. The multicolored hedgehogs with 47 legs give way to a series of established forms and colors, like stick figures, pastel green grass, and houses with triangular roofs. The wild diversity is gone. From now on, it’s crude, habitual symbolism. Most people never relearn how to draw anything interesting again.

This tends to happen in all domains of our lives. We figure out how to do things “well enough” and then get stuck.

One way to think about this is by analogy to what in machine learning is known as mode collapse. Mode collapse is when a generative model (most notoriously GANs) stops producing diverse outputs and instead obsessively reproduces a small subset of patterns that reliably fool the discriminator. We’ve seen this happen with language models. The early models, up until about 2020, were deranged but could write spectacularly surprising prose from time to time. Now the models are much smarter, but they all write in that uncanny AI voice. “And honestly? That isn’t just sad—it’s stylistic trauma.” The wide space of potential ways of thinking and writing has collapsed into a limited mode. I’ve gathered that Roon has been working at improving writing quality at OpenAI, but so far there hasn’t, in my opinion, been much progress on reintroducing novelty and diversity into the prose.

My probably partly false understanding of what’s going on here is that the models get rewarded when they output certain tokens, and once they get smart enough, they learn that they are more likely to get rewarded if they stay inside a small area of the space of potential ways of writing. Through millions of training cycles, they learn to associate going outside of mode with loss of reward.

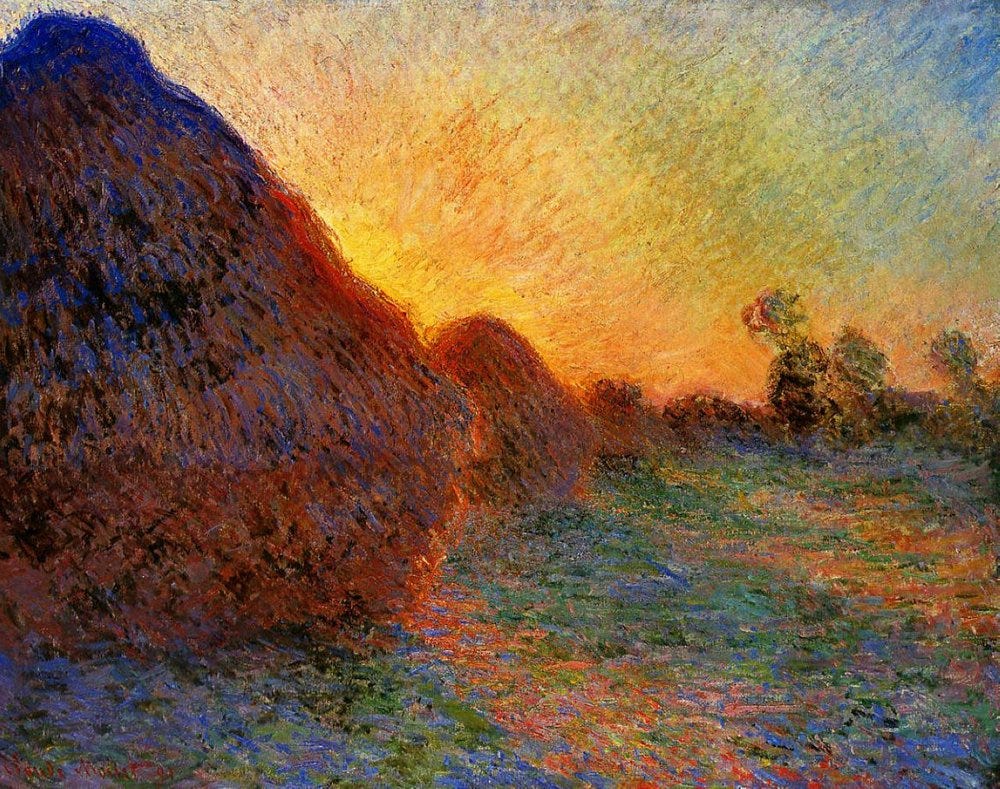

I guess something similar happens with human drawings. Once you learn that grass is “supposed” to be green, it becomes almost embarrassing to make it blue (even though real grass often is blue, as good painters learn when they start to pay closer attention to reality). Once we’ve learned that grass “is” green, we often can’t even see that it actually looks blue in a certain light (and red in another), until someone points it out to us—

Unless we actively push against it, it seems like we will mode collapse like this in all domains. As Andrej Karpathy put it in a recent interview with Dwarkesh Patel, children “will say stuff that will shock you, because you can see where they are coming from, but it’s just not the thing you say. They’re not yet collapsed. But we are collapsed. We end up revisiting the same thoughts. We end up saying more and more of the same stuff, and the learning rates go down.” We get stuck at good enough and then ever-so-slowly backslide. I saw that with our 8-year-old last month. After making predictable drawings for a few years, she had a breakthrough and learned to pay attention to how horses actually look. Then, after she’d mastered a more accurate way of drawing horses, she stopped looking and began repeating the new form until it hardened into caricature.

As Nabeel Qureshi wrote about Karpathy’s remark, people who are able to remain interesting design “their lives to avoid [mode collapse] happening to them.” He suggests they do this by writing a lot and exposing themselves to information that contradicts them or is novel to them:

It seems that when you’re younger, weight updates happen kind of naturally. As you age you have to do this explicitly, which means:

1) reading and writing a lot, to make updates “clearer”

2) having conversations with people, esp people who disagree with you

And on the reading, at least some of the time you need to be sampling from places you wouldn’t normally look. Otherwise the natural tendency is just to read more of whatever reinforces your existing views.

This is good advice. But the hard thing is that this gets more painful the older you get. As you learn more and grow more skilled, there is more reward associated with staying within a limited mode; the opportunity cost of remaining uncollapsed increases.

When I was 20 and played around with writing, no one cared what I did, and so I lost no reputation or income by doing novel things. These days, I have found a mode of writing that is rewarded, and if I go beyond it—which I try to do consistently—I get a salary cut the same day. I’ve seen many writers I know end up losing their edge in this situation. The playful wildness that made them successful gets replaced by increasingly hollow repetition as they struggle to maintain the career they worked so hard to achieve.

I thought a lot about this as I was contemplating writing full-time in 2024. It just seems so depressing when “what you do to survive / kills the things you love” as Bruce Springsteen sings in “Devils and Dust.”

As I was weighing the pros and cons of quitting my day job, I read about and talked to people who have managed to stay interesting for several decades, to figure out what they did to avoid mode collapse. A lot of it is what Nabeel says: they keep learning and consuming novel information, and they write a lot. But it’s instructive to look at what a life like that is like, more concretely.

Take Brian Eno, who I, at least, find remarkably interesting 50 years into his career. When I listen to Secret Life, the album he did with his protégé Fred Again.. in 2023, it sounds to me like one of the most modern and novel sounds in recent years—just as the album Eno did with Roxy Music in 1972 sounded ahead of its time (and is still surprisingly strange and interesting). In between, he invented ambient music, was one of the midwives of the No Wave sound of late 70s New York, helped shape arena rock with U2, and so on. He also wrote interesting essays, made procedural art, invented oblique strategies, and co-founded the Long Now Foundation. Almost at any point in the last 50 years, it feels like Eno’s been doing interesting work!

As I was reading about Eno and others last year, I was sort of hoping to come across a clever trick you could do to keep going like this. But the truth is painful and simple. Eno is able to remain interesting because he’s willing to risk everything he’s achieved again and again.

It is an endless loop where:

Eno does something random that no one is interested in

then, every few years, one of his projects turns into a surprise hit, after which

people come running, asking him to do more of it, offering him large sums of money, which he

turns down, in order to work on something that no one cares about.

With Roxy Music, in the early ‘70s, Eno incorporated synths and electronic processing into rock music, which wasn’t a thing at the time. When that became a hit, Eno got offered large sums of money to tour and make more records like that. But instead he quit the band and started playing classical music with an orchestra consisting of only bad musicians, something that, naturally, exasperated his manager. Then, when his forays into strange noises led to ambient music, his albums with Talking Heads, and No Wave, and so on, people got excited again and wanted to pour money at him to do more of that. Eno decided to go to Thailand to work on light art.

A reason it is hard to have both a creative career and remain interesting, then, is that it is a high-risk strategy. There is probably a lot of survivorship bias in the sample I studied (meaning: most people who were wild enough to blow up their first success never got around to a second success, and so there are no biographies written about them). Looking at Eno and concluding that blowing everything up again and again is the key to remaining interesting might be true. But it might also be true that it is more commonly the key to losing everything.

As someone who is well-positioned to blow up a good career, I don’t think we should read too much into the survivorship bias, though. If these risks are necessary for creative work, then not taking them means you automatically lose; and it is possible to take these risks in a somewhat controlled manner. It is clear to me that Eno did so. He might like to give the impression that he was simply following his curiosity, but it was at least partly calculated. Especially in the early years of his career, he did the obvious, rewarded thing more often than he did later. But he did so in order to position himself to do wilder things longterm.

It is sometimes necessary to play conservatively, to be able to pay the bills. But if you’re wired like me and care deeply about doing good, creative work, you must never lose sight of the hierarchy of values. If writing full-time makes you write fewer good essays—as has happened to some people I know—then writing full-time is the thing to sacrifice, not the essays. If you have a hit and can build up some savings, that is meant to fund bigger risks going forward, not keeping up with the Joneses.

I’m not saying this is how everyone should live. In fact, I think it is very, very important that some people optimize for money—it makes them do valuable work that I would never bother doing. And for the same reason, I think it is important that some people optimize for status or consensus or risk aversion.

But if you want to avoid mode collapse, it will require sacrificing other things. It will require saying no to lucrative projects in order to explore things no one cares about. It will require looking stupid. It will require feeling uncomfortable. And it will require, in many cases, living hand to mouth from time to time.

Life update

Johanna, the kids, and I spent two weeks in Sweden over Christmas and New Year’s.

The first part we spent near the border to Norway, where Johanna grew up. The kids played with their grandparents, and Johanna and I walked along the river, and went shopping for Swedish books. On Christmas Eve, Johanna’s mother and I took the elevator down into the basement and I got to put on the coveted Santa costume and do my routine. I was a very grumpy Santa who played piano whenever attention drifted away from me to the Christmas gifts. It felt good to not be writing—I haven’t had a proper pause in 4 years; I needed some time to step back and think about where I want to go in the year ahead.

Am I at risk of mode collapse? Am I repeating myself and becoming too conservative in what I allow myself to work on? Am I habitually doing what I had to do to get here, rather than looking clear-eyed at the possibilities that actually exist now?

In bed at night, I made a list of some alternatives, things I could work on. I always like to get a lot of options on the table so I can get a better sense of the possibility space and not get stuck on the first thing that comes up. I could:

Write a book. I have very mixed feelings about this. On the one hand it feels like a natural step—I’m at a point in my life where I could do it properly, with a good team of collaborators and a reasonable advance, so I could invest a few thousand hours into the project. But because it feels so natural, and many people urge me to do it, I am uncertain: I have such difficulty hearing what I feel when there are strong external reasons to do something.

Compile an essay collection.

Get back into programming. It feels like there are so many fun little art projects I could throw together by vibe coding. I have this old dream of making essays the size of cathedrals—making very ambitious essays with bespoke homepages for each, so I can leverage code to do things that haven’t been possible before. I think the cost of doing it has now dropped to the point where that vision becomes affordable for me. But I haven’t programmed for 6-7 years now, so I would need to set aside considerable time to bring that part of my brain back to life, so the ideas start flowing.

Do a book club. Maybe Proust.

Do meetups. Or make it easy for others to arrange meetups with readers from the blog.

Machine translate the full text of Grothendieck’s Récoltes et Semailles. It seems like the attempts to get it translated have stalled, and per my experiments lately, I think it is now possible to set up a pipeline to make a passable translation. Could publish it as an ebook + a homepage with the original text available if you click on a passage.

Do more small playful collaborations with others.

Gather a group of independent researchers, writers, and artists on the island, rent all the houses around our farm, and have a summer camp where we work, have seminars, and swim.

Do reportages and interviews. And by that, I don’t mean I should write in those genres, I mean I want to spend more time travelling and talking to people to collect material that can enrich my essayism. I’m thinking something along the lines of Werner Herzog’s documentaries. It would be fun to visit the production of Ruben Östlund’s new film (which he’s working on in Hungary right now). It would be fun to go to England with Johanna and look at gardens and interview Dan Pearson, Arne Maynard, and others. I notice this idea scares me—it is a different process than the one I’m used to, and I’m uncertain whether I have what it takes to write good essays in this way. I might end up plowing months into it, and come out on the other end with little to show for it. I’m afraid that I won’t be able to handle the complexity of the logistics and still produce the steady stream of essays necessary to pay our bills, and I’m afraid the work won’t interest others, so it ends up eroding the support I’ve built up over the years. This fear seems good!

I note that the last idea attracts me the most. I want to meet more people and write in a higher-resolution way. Of all of the ideas above, it is the one that will force me most outside of my comfort zone and into novel situations.

Having articulated the idea, the fear seems largely unfounded. There are some risks (there are always risks), but they can be mitigated. I can try things in small, low-cost ways. I can carve out part of the week to work on illegible projects and part of the week for doing work that keeps the food on the table, until the illegible can replace the legible. Once I start sketching out the ideas, talking them over with Johanna, I can see solutions and possibilities that I hadn’t considered.

I’m very glad I took the time to think this through. And now I’m glad to be back on the island, looking out at the snowy woods outside my office, listening to the kids through the wall. It feels good to be writing again.

Thank you Johanna for the conversations that led to this essay. The copy edits were done by Esha Rana.

What a sensational piece. As a full-time novelist in the US, and the only income producer in the family, I spend a lot of time considering all of the above. I love how you brought Brian Eno into it. For me, it is indeed about striking a balance. I need to stay in my lane to some degree, meaning I can't abruptly change genres or write something that doesn't have page-turning momentum without risking my income, but I can't simply fall into a cookie-cutter pattern or I risk casting my soul into the depths of Hades. In the end, I find I have to keep mixing it up, pushing myself, taking giant risks, so long as those risks are calculated in a way that I can continue to make a living as a writer. Thanks for sharing such eloquent thought, Henrik! Glad I found you.

Henrik, thank you for this exposition, the idea of 'mode collapse' so beautifully described. I love the implicit exposition of your inner process, appreciating the roots of interest, curiosity and desire as they reach into conceptual mapping, strategy and verbal expression, where they might just homogenize into the collective chorus. I rode along with you easily, and sure enough, in the last few paragraphs you referenced the promptings in your own experience that keep creativity robust and potent: the intuitive juice, the attraction and excitement, regardless of fear, that keeps you awake and alive. There's today's multicolored hedgehog with 47 legs! Wahoooooooo!