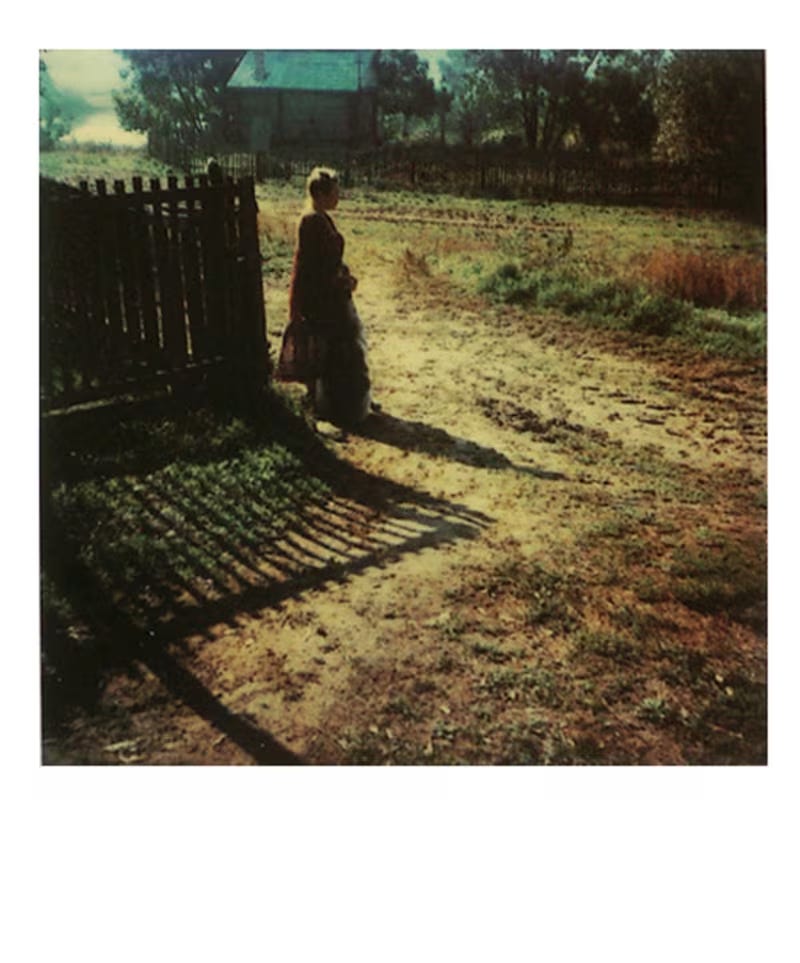

A polaroid by Andrei Tarkovsky

I had a discussion about writing with Johanna, my wife and collaborator. The context is that she is in the early stages of a new writing project—she knows the rough outline of the ideas she wants to cover, but the actual content of the essay is fuzzy. She asked me what I would do in this situation, to go from rough idea to first draft. Here are some bullet points from our discussion:

I would be tempted to start writing the essay, but that would be a mistake. Everyone is different, but for me, writing essays is like shooting a documentary. I need to record the raw footage before I sit down and edit the film. And I want to have more footage than I will use, often a lot more.

By raw footage, I mean actual prose—not outlines, not summaries—about the topic I want to write about. But I don’t mean essay-grade prose: that is too costly to write; it would be like making the actual film. I mean rough attempts written as fast as I can, as well as excerpts from my journal, transcriptions of conversations I’ve had about the topic, and quotes from books I’ve read, and my comments on the quotes. Very rough and pragmatic stuff.

And importantly: this rough, raw material needs to be “at the same resolution” as the final essay. Again, imagine you are making a documentary—let’s say, you’re Werner Herzog, and you’re making Into the Abyss. The opening scene of that film is “Herzog interviewing a reverend who in 15 minutes will be accompanying a young man to his execution.” If that summary was all Herzog had, it would be impossible to know if the scene deserves to be in the film; it all comes down to the detail. The reason the scene belongs in the film, and in the opening of the film, is that the reverend ends up telling a story about a squirrel—and not only that, it belongs in the film because of the way his face looks before, during, and after he’s told the story. Herzog only knew these details of the scene until after the interview had been shot. So the decisions about what should be in the film couldn’t be made until after the raw footage had been collected. It is the same, for me, when it comes to essays. I can write all the outlines I want (and I do, because they are a tool that lets me remember ideas that I haven’t had time to unpack yet), but there’s little point in writing the outline until I’ve made full length sketches of all the ideas in it, and all the examples and anecdotes I could use and so on.

But isn’t that the same thing as writing it? I guess it might be for some. But for me, if I think I’m writing the essay, I get all tense and start polishing the prose and put in way too much effort into ideas and stories that might not deserve to be in the essay. And when I do that, I get reluctant to cut the material, which means the essay gets bogged down with mediocre stuff. I need to write rough notes and so on, so that I can go really fast and try many ideas and see them in high resolution, before I edit together the essay and polish the prose. During the preproduction of an essay, I want to write 1,000 words an hour or more. I want to go fast enough that I can afford to try many more ideas than I will end up using.

Johanna points out that I tend to create and collect raw material in a few different ways: